- Home

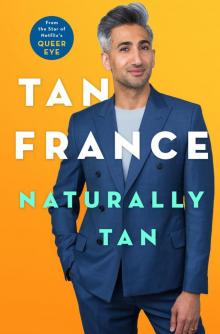

- Tan France

Naturally Tan Page 2

Naturally Tan Read online

Page 2

To get back home from school, we had to walk on this one road, and there was no getting around them. We looked at each other. Do we go home? Do we run back to school? We walked back to school. We waited. We walked back. They were still there. It had been over an hour.

We had to get home somehow. Finally, we were like, “We’ll have to go through and pray they don’t attack us.” We literally prayed. When I was a kid, I wholeheartedly believed you could pray your way out of a bad situation. Maybe this was the moment I accepted the fact that this was not in fact true.

We knew there was no way on God’s earth they would ever let us get by. It was the most horrible feeling, walking up to them, the whole time thinking, Fuck, fuck, fuck, fuck, fuck. I felt physically sick, my legs starting to turn to jelly. I put on the front of a strong, determined kid, but inside, I was just thinking, Tan, don’t you dare shit your pants. These are the only school pants you like right now.

When you’re a kid, and you see people who are eighteen years old, you see them as adults. These were sixteen- to eighteen-year-old boy-men, and my brother and I were probably eleven and thirteen at the time. There were at least six of them, versus the two of us on our own. I’m no bookie, but gurl, these were not great odds for us, and some real-real was about to go down.

As we got closer, my brother, bless him, was like, “You run. I’ll deal with it.” We knew there was no way we’d be able to beat them up ourselves, so the only way to solve it was for me to run home as quickly as possible and get help. In hindsight, I wish I had just stayed with him and tried my best to fight them off, or at least encouraged him to run and for me to stay. But he was nowhere near as fast as I was, and in my culture, the older siblings must always protect their younger siblings.

We were only about fifty meters away from our house, which was just around the corner. As we drew closer to the gang of fuckwits, I sprinted around them, into oncoming traffic, ducking and weaving, and lost them. I was home in a heartbeat and ran through the door screaming, “Help! Help! They’re going to kill him!”

The look on my dad’s face. I had never seen that look before and never did again until the day he passed. It was a look of absolute horror and rage. He knew without me saying another word what was happening. His greatest fear was being realized. As a hopefully soon-to-be parent, I pray I never have to experience this kind of terror.

My dad got up and started running toward the street. Pakistanis usually don’t wear shoes in the home, so he ran right out into the street barefoot. Mind you, in England, it’s usually cold and rainy and wet, but he ran out there without any selfish concern, as any parent would. I wanted to go, too, but my mum stopped me. Apparently, my dad ran up to the pack of boys, yelling, and they fled. My dad saved my brother, but not before my brother had taken a severe beating. All because we were brown and we needed to get home.

When I was a kid, my fantasy was to one day be old enough and strong enough to hire a van, round up all the bullies in the van, and give every brown person a turn beating the shit out of them. My greatest dream, as a kid, was so violent. I’m not a violent person, and the fact that I would ever dream of this is a good indicator of how rough it was being a person of colour. My biggest fantasy was to be able to take my revenge, which is a seriously screwed-up mentality for a child to have. I once shared this with a friend who is also brown, and he was like, “That’s literally my dream, too! To round them up and have them experience what they’ve done to us.”

I had another dream as a kid, which angers me now. But I’ve talked to many friends of colour who have told me they shared the same dream, and that is to wake up white. I first had that dream when I was very, very young, because I worried constantly that if I went outside the house, bad things would happen to me. It’s something I knew I couldn’t do anything about, but it did keep me up at night. I didn’t tell anyone at the time, as I didn’t want to appear weak. Also, none of my siblings seemed concerned that we were different from anyone else, so I thought it best to just bottle it up. I remember sometimes getting anxious when I knew I’d have to walk to school alone, like if my brother was sick. In those instances, I would practically run to school, all the while looking around to make sure that no one was going to attack me for my brown-ness before I got to my destination. I would avoid alleys and often tried to stay close to women or families and pretend I was with them. All the while, I would think, Why the heck was I born this way? If I had been born white, life would have been so much easier. I fantasized all the time about what it would feel like to be a white person—nobody would ever comment about your race and how much that must impact your confidence and mood and attitude.

The only nice balancing point was that, in school, nobody ever caused us any issues. I remember incidents of down-low racism, where something would happen and a classmate would say, “Fucking Paki,” and then turn to me and say, “Not you. We like you. But other Pakis are the worst.” And at the time, I accepted it, because I thought, At least they’re not calling me that! Now, I wish I could go back and tell teenage Tan to stand up to their stupidity and ignorance and challenge them. To show them how ridiculous of a statement that was—that because they know me, I’m okay. If only they took the time to get to know others like me, to see just how not-different we all were.

But unless somebody pointed out aloud that I was brown, I often forgot. If somebody called me a Paki, I was like, Oh yeah! I forgot. I let my guard down for a sec and totally forgot that I should be more aware of it. I remember very distinctly forgetting a lot of the time, until somebody would very rudely remind me that I was indeed different and how that was not okay.

I remember thinking I always had to be polite, always be nice, always be kind. You can’t be another crazy brown person who’s upset; you have to show them you’re just like they are—bright, white, and smiley.

Now I can process it differently, and looking back, I do feel annoyed at that injustice, because sometimes, no matter who you are, you really do just want to shout and scream about how crappy it is to be treated as less-than. But people of colour are frightfully aware that one person’s actions represent the actions of all of our community. A white person can shout and kick and scream, and people will say, “Gosh darn it, this is why we don’t like Jack,” but they aren’t going to say, “This is why we don’t like white people.” On the other hand, if I did that exact same thing, it would be, “This is why we don’t like brown people. Brown people are always so temperamental. They really should go back to their own country.”

Speaking of that—bitch, this is my country. I was born and raised in England. Great Britain colonized my family’s homeland, and then that led my people to have the right to come to the UK to settle and have kids in that country. If the Brits could come to South Asia (and many, many other lands) to claim it as their own, then by gosh, I have the right to call England my home, and I will not get out because I’m told to … and neither will the rest of my people.

I used to think a lot about how I would react to somebody if they ever tried to fight me. I knew even then that my trying to fight those people was going to achieve nothing, just as my swearing at them was going to achieve nothing. The only way I could make it easier might be to level with them as human beings and try to explain it to them. “You think I’m the devil because I’m brown, but actually, I’m just like you. Yes, my skin and my food might look different, but if you got to know me, you’d probably really like me.” Then I would ask them, “Why are you doing this? There’s no reason for you to have this hatred for me; it’s unfounded. Let’s talk about how you came to the conclusion that I don’t belong here. And tell me how, exactly, white is right?”

When I was younger, I distinctly remember feeling quite alone. My family wasn’t the kind of family that talked about feelings. Well, we told each other if we were mad, but not if we felt something more complex. It’s not really the South Asian way to talk about feelings, so it didn’t even dawn on me that I should chat to my family or friend

s about feeling lonely because I never saw our people represented in the media.

I didn’t see myself reflected anywhere in popular culture, and a lot of us get our feelings of normalcy or approval or validation from what we see around us. Everywhere you look, you see a lot of Caucasians, and you think, It’s great to be white. On TV, in magazines, on billboards. It’s mostly white. You see black people and you think, Okay, the tides are turning. You see lesbians and you think, Good, we’re shedding light on this. But I do distinctly remember thinking, Holy shit! I don’t see anybody from South Asia on TV who’s gay, and that really started to freak me out.

I thought if I ever came out—because for many years I thought I could hide it forever—it would be a shock to everyone around me because it wasn’t something they had seen before.

There was a western British show called Queer as Folk, which came out in 1999, around the same time as Will & Grace and the original Queer Eye. I remember thinking, Okay, I’m not alone. There are gay people on TV. But there was a distinct demographic that was missing. I longed for the day when I’d see a bunch of gay South Asian and Middle Eastern men and women on TV and in movies, but it never came. Where were their stories? Where were our stories? Had we been forgotten? Did no one want to hear what we had to say?

It took a very long time for this to change. It’s shocking that in 2018 I’m one of the first people to do it, but I’m glad things are finally starting to evolve.

When I first considered being on the show, the very idea of representing a community scared the shit out of me, and that was just the LGBT+ community—adding on the responsibility of representing the South Asian community caused me even greater fear. I worried that everything I did and said would be seen as my speaking for the entire South Asian community. That if I said something wrong, people would think even more negatively about Pakistanis than they already might. That if I did something wrong, people would assume all Pakistanis must do this or think this.

I’m hyperaware of the fact that when I speak, I don’t speak for just me. The press reminds me that everything I say becomes either the voice of the gay community or the voice of South Asian / Middle Eastern men.

Beyond this, I was so worried about how I was going to tackle religion. I knew that no matter what, I was never going to be just Tan France. The press was always going to refer to me as Tan France, the gay British Muslim. They never introduce Antoni as the gay Polish Christian. Never. He’s just Antoni.

Religion was something I never wanted to talk about and still don’t. That’s my gosh damn business, but the press insists on referring to it in almost every interview or announcement. I was right to worry, as it was something we had to push for every interviewer not to ask about, since it was usually one of the first things they wanted to discuss. I’m more than happy to represent South Asians, but when it comes to religion, that’s too personal of a path. I never want to claim to represent a religion or its practices.

So I was so worried to be one of the first, as I knew it would be a hard pill for many to swallow. I knew that I would come up against major opposition from people who wanted to silence me and to pretend that we don’t have this issue in our communities. That what I’m doing is “promoting and encouraging” this lifestyle.

No! What I’m doing is a job that I love. A job that makes me happy and that just so happens to offer a perspective that’s never really been shown before. No statements are being made. There is no political or cultural agenda. There is just me, being visible and unapologetically authentic.

I hope it provides comfort to kids who have never seen any version of me on TV before. I hope they think, Tan managed to make things work, and he’s happy and open about who he is. I can be, too.

I hope I give them some hope.

JEANS

Ever since I was a little boy, I’ve lived in jeans. Although shalwar kameez was our wardrobe expectation at home, I had a bunch of Western clothing to wear for school, and I would naughtily change into it every opportunity I got. In my adult life, I enjoy denim just fine, but I loved it as a kid, because I saw it as playful and experimental.

I’ll admit I had a closer affinity than most to jeans, because my granddad owned a denim factory farther up north in England. As a child, I visited him there every summer, and I found it fascinating. The factory was very large, four or five floors, and filled with hundreds of machines laid out in rows. During those visits, I could explore a version of my life that wasn’t possible anywhere else.

My granddad showed me everything, starting with the table that held a massive bolt of denim fabric that was then rolled out and cut to size. That piece would be passed on to the next station, where someone sewed a seam. Then on to the next person, who would sew another seam. Each garment would take about ten minutes to make. The reasoning for this process is that if you had one person making an entire garment from start to finish, it would take three or four days, but through piecework, because everyone is so efficient at their one specific task, it takes ten or fifteen minutes. I found the women who worked there fascinating—I’d never seen anything like it. You wear clothes your whole life and never think about how they are produced. But I had this intel that I thought nobody else had, the privilege to see all the work and thought that goes into the things we wear.

My granddad had a licensing deal with Disney, and his factory-made jeans, denim jackets, and sleeveless jackets were printed with Disney characters. I remember thinking, What? I can make my own Disney clothes? I wanted to be just like these women one day, screening Mickey onto T-shirts. I saw it as a way to be creative.

As a kid, I wasn’t encouraged to be creative. Most children are just told to wear what their parents buy for them—but I was not that child. I saw so many ways to express myself sartorially. I would take as many things as possible from my granddad’s factory. I had so many Mickey and Minnie jeans and Pluto jackets. I took every available option in every colour that he’d let me have. I wanted to have as many pieces as possible at my disposal so I could change it up regularly.

I was that kid who changed outfits multiple times a day depending on my mood, all the while knowing that the only thing my mum wanted me to wear was my shalwar kameez.

When I was six, seven, eight years old, I wore multiple looks throughout the day. “It was such hard work to get you to try to stay in the same outfit all day,” my mum told me. “You would change depending on what you wanted to do. You would insist on changing for dinner, and then for our evening hangout; if you were going to be playing, you would insist on changing again.” When it came to laundry, it was a nightmare. But I had so many looks in my mind that I wanted to put together, much to my mother’s dismay!

For playtime, my look of choice was baggy jeans and T-shirts. For dinner, I dressed up in a button-up, done all the way up, and my school trousers. I don’t know if I thought my family would pull a “tricked ya, bitch” and take me to the Ritz for dinner, but that was apparently what I was preparing for.

I had only a finite number of tops and jeans, and I wanted to come up with new and different ways of wearing them. I had an industrial sewing machine, and I used it to change things up. My grandfather had taught me how to sew during my summer visits with him, and back at home, I added a velvet collar to a top without a collar that I knew would benefit from it, and I added darts to pretty much every button-up shirt I had to change the way they fit.

Fashion became my thing, because I couldn’t express myself any other way. I wasn’t a super outgoing kid. I wasn’t loud. I was likable because I was friendly, but I hadn’t really developed my own personality yet. So I used clothes to show the world who I was. Clothes were the only way I knew how to articulate myself. I never thought it would be my job one day, or that I would wind up working in this industry.

In our culture and community, expressing oneself through fashion was not considered cool—nor was it seen as something boys do—and I found that very difficult. Whenever I dressed myself, I noticed some snick

ering behind my back. I remember feeling hurt when I heard snickers and comments from family members.

There was one time when I overheard my cousin asking another cousin why my family let me wear that jacket with Minnie Mouse on it when it was clearly meant for a girl. I had never even considered that I shouldn’t wear that. I loved it and wanted to wear it. It was one of the first times I realized that people weren’t approving of my differences, and it was jarring. No one would ever tell me that I looked stupid directly to my face, but they would kind of make fun of me, like, “What the heck has Tan got on now?”

I couldn’t say to anybody, “Hey, guess what? I really like boys,” so my style was my way of saying, “I’m all about being who I want to be.”

Once, we were headed to a family wedding. Everyone else was wearing these suits, and I wouldn’t have been caught dead in the suit that everyone else was wearing. It was boxy, unflattering, and just all-around blah. Even as a kid, I wanted to stand out and make a style statement. On this occasion, I wanted to wear a sports jersey. It was one of those oversized, perforated Starter jerseys for the Mighty Ducks—I didn’t even know what team that was or what state they were from—but I saw someone on MTV wearing something similar and so I wanted to rock it, too. I wore it with high-top sneakers and jeans, because it was cool. Or at least I thought it looked cool. It was actually so inappropriate for a wedding. That’s what I wore to somebody’s wedding.

Because I was constantly so headstrong about what I wanted to wear, my parents learned to back off and let me do my thing. They knew that if they didn’t, I would sulk all day and cause a scene. I was always polite and kind, but when it came to getting my own way, I knew how to manipulate the situation. I was the youngest sibling. I very quickly learned how to get what I wanted.

Naturally Tan

Naturally Tan