- Home

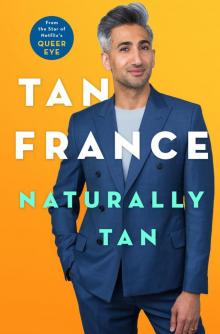

- Tan France

Naturally Tan

Naturally Tan Read online

Begin Reading

Table of Contents

About the Author

Photos

Copyright Page

Thank you for buying this

St. Martin's Press ebook.

To receive special offers, bonus content,

and info on new releases and other great reads,

sign up for our newsletters.

Or visit us online at

us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup

For email updates on the author, click here.

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To my perfect husband, without whom none of this would have been possible. Me and you, forever.

SHALWAR KAMEEZ

Straight people love to ask, “When did you know you were gay?” Maybe some people do have an epiphany. I am not that person. For me, when somebody asks me this question, it’s the same as someone asking, “When did you know you were a boy?” or “When did you realize you were a human?”

Because I breathe.

I’ve always known.

It sounds cliché, but I never had that Oprah aha moment. I always knew that women weren’t for me. Don’t get me wrong—I’ve always loved women, in that I wanted to surround myself with females, and they are the people who have molded who I’ve become, but there was never a time when I thought a woman was a viable option for my romantic future. I also never thought that a man was not an option. Even when I was very young, I assumed I would get married one day and it would be to a man. Why wouldn’t it be so? It was men I was attracted to and loved, so it stood to reason that I would eventually marry one. I never thought that might not be legally possible, nor did I think it was problematic. I was very matter-of-fact about it, as I was with most things in my life, and still am. Throughout this book, you’ll realize that maybe I’m not the “zero fucks given” kinda guy, but I’m definitely the “very few fucks given” guy. It’s a quality I like about myself and don’t plan to change anytime soon.

I grew up in a small English county called South Yorkshire, which is in the north of the country. It was mostly white; there were maybe ten other South Asians in my school and one black student. My parents were both born and raised in Pakistan until they moved to the UK with their respective families in their teens. My dad’s family moved to the north of England in the 1950s with very little money. Eventually, he saved enough money to buy a home and start a business, and he became relatively successful. My mum’s family was already in a nearby town, and my parents met and—this is very bold of them—had what is a called a “love marriage.” In a culture that favours arranged marriages, sometimes even among cousins—(Calm the frack down. I know, I know, that sounds crazy, but I can’t get into that right now. More on this later.)—this was an entirely unconventional way to start their life together. We lived in a home adjoining my father’s brothers, so I was raised alongside female cousins that I one day might be called upon to marry.

Our home wasn’t super religious, but we had a profound cultural connection to our Muslim heritage. Every day, I would get out of school by 3:30, get home at 4:00, and then go to mosque, where I would stay until 7:00. It was like that every day, Monday through Friday, and weekends, too. Even when white school was on vacation, it didn’t matter. Brown school doesn’t take any time off.

At the age of six or seven, we started to wear modest clothes called shalwar kameez. The pants have an elasticated waistband. If you open them up, they’re massive, one size fits all, and they are really bunchy and baggy, tapering toward the bottom with a cuff like a harem pant. Over them, you wear a tunic—for men, plain and over the knees or longer, and for women, looser still. As an added layer of modesty out of the house, women also wear a jilbab—essentially, a large sack. There could be a gust of wind and still you will not see what you should not be seeing.

The only time I was permitted to wear anything other than shalwar kameez was at school, where I wore a uniform, or when we broke out the “fancy Western clothes” permitted for events like weddings or birthday parties.

Beyond this, we were supposed to conduct ourselves with modesty in all aspects of our lives. We weren’t allowed to have sleepovers or hang out with our friends outside of school—and we weren’t allowed to date. Of course, this was no problem for much of my adolescence, because I didn’t like girls. Actually, not being able to date was a blessing at the time, as it made it so easy to cover up the fact that I wasn’t into girls. I just couldn’t date. I’m single because I’m not allowed to date and not because I don’t fancy girls. So that’s that. Nothing to see here, folks.

There were five of us—I have two sisters and two brothers—and I was the baby. Out of all my siblings, I was always the surest of myself. My parents worked a lot, and so when they weren’t around, I watched a lot of TV that was not permitted, like Melrose Place, Beverly Hills 90210, and ER, all of which had much more mature subject matter than a child should be watching. They dealt with subjects like sex and drug use, which my parents would have been completely shocked to discover I understood, never mind that I was learning about these things from TV. These topics were never discussed in our culture. Because I watched so many shows, I became weirdly worldly wise. My vocabulary was different; I knew things even my oldest siblings didn’t know. I was definitely the cockiest one of the family. I would correct other people’s spelling and grammar and the way they’d speak. I was the obnoxious sibling. I was a nightmare.

It was clear from an early age that I was “different” and that I had a particular affinity for personal style. Growing up, my favourite movie was Dirty Dancing, which no other eight-year-old boy was obsessed with. (Their loss. That movie is still incredible and holds up like no other.) I also had lots of Barbie dolls, but no one outside the house knew about that, which is probably a good thing, as my school was definitely not ready for that in 1990. Weirdly, my dad got them for me. (I know that sounds insane, but here goes.)

My dad and his brother were super close, but strangely competitive. They each had children of similar ages, and the cousin closest to my age was female. She and I were in the same classes throughout school, and we were encouraged to compete with each other when it came to our grades and exams. That competition spilled over into gift giving from our parents.

When my dad learned that my cousin had been given a Barbie house and a Barbie doll, the following week I had a bigger Barbie house with five or six Barbie dolls. I also had two Ken dolls, one black and one white, and a black doll called Cindy who was a popular UK Barbie knock-off. No one saw this as peculiar—which, looking back, just shows how oblivious we all were to Western culture and how that would have been considered out of the norm for most sons to receive. I, however, was over the freaking moon. It felt like all my Christmases had come at once. I wondered when my dad would realize that playing with Barbies wasn’t what he might have wanted for me, so I always did it in secret. I pretended to be totally unfazed about the Barbies when anyone was around, but as soon as the coast was clear, I’d run up to my bedroom and play house with my new favourite toys. It was a really happy time.

When I wasn’t at home, I remember hating school. I found it boring, and I had no desire to learn. I liked the social aspect—I wasn’t popular and I didn’t have a crew, but I had friends. I had a couple of close male friends, one South Asian and one white, and a really close South Asian female friend. It was pretty easy to make South Asian friends, as there were so few of us that we banded together. Strength-in-numbers kinda s

hit, because you knew you needed those numbers outside of school, in case it was one of those “special” days when the racist bullies were outside the school grounds waiting for their next attack.

Luckily, I always had someone to sit with or talk to. I felt like I was part of something, and I wasn’t concerned about dating or the future. I was fun and funny, and I could make people laugh in class. I think I was liked enough during school hours, and no one at school ever caused me any issues.

Even though I hated academia, I did well in class; I was a solid A/B student. I did no homework, and I did only the minimum required to get through, but it always worked. I remember lording it over my siblings that they had to work so hard for grades (I really was a nightmare with my sibs), and I was able to do it all without revision (our word for studying). I didn’t have to revise; I could just watch TV instead and then take the exam and do very well.

Outside of school, I didn’t have much of a chance to have a social life, as it’s not considered appropriate for South Asian boys and girls to mix freely. Even if I had a group of all-male friends, they couldn’t come over because I had sisters. At the time, I thought this was so lame, and I was annoyed at my parents for it, but now I see it’s just smart, man. As an adult, I now understand they were onto something. I will do the same with my kids. Shit goes down sometimes; you never know! My kids can have sleepovers at our house, where I know that no man is going to do something that he shouldn’t. Do you think I’ll trust my kids to go stay at some rando’s house, with adults I don’t know? Heck no.

By the time I was a teenager, I started to panic. I remember watching a movie with my two sisters, featuring a Bollywood star who was very, very handsome. My sister said, “I love him. I want to marry him.” I remember saying, “I love him, too. I’m going to marry him, too.” And they said, “No, no, boys don’t marry boys; boys marry girls.”

For the first time ever, I thought, Holy shit, is something wrong with me? Why can’t a boy marry another boy? And why do I want to marry a boy so badly?

They weren’t being mean; that was just what it was like back in the day. I was eight and they were teenagers, and that was the first time someone vocalized it for me. That was the first time I ever thought, Oh, shit, I’m different, and the thing I thought was okay is not okay as far as other people are concerned.

As a teenager, I remember having crushes on a couple of people in particular at school. The first time I ever actually realized that I was gay—and by that, I mean I actually associated the word with the feeling—was when I was around thirteen years old, at recess. A friend of mine was playing basketball in the schoolyard. It was a really warm day, so he took his shirt off. I remember looking at him and his muscular physique and thinking he was the sexiest man in the world. That was literally the word I remember thinking at the time … about a thirteen-year-old “muscular” guy. Oh my.

I never thought, I need to put a stop to this. The only thought I had was, I hope I can continue to live this way, but I’m going to have to hide it as much as possible. I came up with a plan I thought would work: I would marry a woman who was my friend, and we would have an agreement. She could date whomever she wanted to date, and I could date whomever I wanted to date. She would be happy, and I would be happy. I really thought this would work.

I was clearly not as smart as I thought I was.

In my early twenties, I thought, I’m going to have to find a way to come clean. I knew I was getting to the age where “good” Pakistani boys start to settle down and get married. I could probably make it to thirty at the very latest before people really started to question why I hadn’t found a girl and gotten married yet.

I truly never felt wrong about my feelings for men. That’s why I still wholeheartedly know there is no nurture involved in any of this. It was all nature; it was all the way it had to be, because it never seemed wrong. I never felt like this was something I had willed, nor was it something I had any control over. It was as simple as lust and love, both of which were completely natural to me.

I did think that when I finally started to date a boy, that’s when I would realize there was something really wrong and that I was doing something that was against my community, my culture, my religion … everything. I thought I would have a moment where I would feel like I was committing a massive sin.

I have yet to feel that.

Because I grew up in a South Asian community, where you are often reminded you’re acting or behaving in a way that would either appease or displease God with everything you do, I expected to feel like I was going against everything my faith stood for. But thankfully, as I grew older, I started to change my mentality. I expected that the first time I kissed another man, I would feel this instant pang of guilt or nausea that would indicate that it was all wrong and that I should stop immediately, but that moment never came. I couldn’t imagine that me loving somebody could trigger such an adverse reaction from God. None of us knew, of course. But I truly felt like I wouldn’t be punished for loving somebody unconditionally. What could be wrong with that?

But as a kid, this was a tough thing to wrap my head around. This is the case for many gay kids, especially if they’re raised within a certain culture of faith. The ideas of heaven and hell were ingrained in my upbringing, as they are for most people in my community. “If you do this, you’ll go to hell, but if you do this, you’ll give yourself the best shot of not going to hell.” It’s very much fear-based, and I’m glad that I was able to see that loving somebody didn’t mean hell was my only option. I’m sure there were many other things I was doing that could have damned me to hell when I was younger, though. Should I go into those? Yeah, probably not. I’m trying to keep up the “good boy” act, and I don’t want to ruin that so soon in this book. Read on. I’m sure I’ll fuck up that notion for you soon enough.

When I was in school, I always tried so desperately not to cross my legs, even though my legs were begging to be crossed. If I’m really honest, they wanted to do a double cross, which, as we all know, would be such a clear indication that I was into other boys.

I remember very, very early on, I crossed my legs that way once, and a family member said, “Hey, Tan, don’t sit like that. Girls sit like that.” I couldn’t have been older than six or seven, but I was like, Oh, shit. Why am I doing that if only girls do that? Is something wrong with me? I tried to train myself to cross my legs the way men cross their legs. I struggled with that almost as much as I struggled pretending to give a shit about watching football on TV, when I clearly just wanted to watch reruns of Golden Girls and hang on the lanai, eating cheesecake with those broads. I remember thinking, But it’s more comfortable for me to cross the other way. Who cares if girls are doing it and boys aren’t?

Over the years, I learned to hide away any trait that might give away my sexuality, because I was too busy trying not to make my ethnicity such a big issue. I didn’t need a fucking double whammy in my life. I was too busy being brown to be bothered about who I’d eventually end up wanting to marry. I experienced a lot of racism as a kid, not necessarily at school but with people who lived in my town. I spent so much time trying not to get attacked for being brown; there wasn’t a lot of headspace to focus on not seeming gay.

We would get called Paki a lot, which is like our version of the N-word. It’s a horrible slur for Pakistanis and really painful to hear. Simply getting from home to school and back was very difficult. There were these horrible people in my hometown who would cause us absolute hell. Some were my own age, and some were older. They traveled in a pack, and if ever they saw my siblings or me, they would chase us and throw things and call us Pakis. As a group, we had safety in numbers, but they would try to get us on our own. If you were walking along by yourself one day and you came across them, it was going to be a really shitty time for you.

I had a couple of Pakistani-British friends who I walked to school with. Every now and then, the local bullies would push us around and taunt us. Nothing violent, b

ut a light shoving around to get us geared up for the day ahead. Thankfully, they never beat me up, but they did push me around and take my possessions, and it was still a horrible thing to go through.

Because of this, my family wasn’t comfortable with us going outside the house except during school hours. Understandably, my parents were too scared of the racism we suffered in our town. Across the road from our house, there was a little convenience store, which, in England, we call a corner shop. We couldn’t even go there on our own, because the shop sold cans of beer, and the bullies liked to hang around and drink their beers outside of it.

I distinctly remember if I needed to run across the street to get something, I would go as quickly as possible while my parents watched from the window. How horrifying to think they had to watch their child cross the street just to make sure he wasn’t going to get beaten up for being brown. At the time, we were so matter-of-fact about it, and it didn’t faze me. Looking back, it was fucked up, and I never want any family to go through that again.

I was a really short kid, usually the smallest in my class and in any group setting. It took me ages to grow. Beyond this, I was a really skinny kid, which made me an easy target. But I was good at running really fucking fast—my hundred-meter sprint was bananas. Racism sucked, but it encouraged me to run faster than the bullies. This is the only silver lining you’ll find in this chapter.

One day, I was walking home from school with my brother who’s the closest to me in age, just two years older. He was around thirteen years old at the time, and taller than I was, around five foot five. He was a little portly, with super curly short hair. We were near the house, probably only two minutes away, when we saw this group of bullies coming toward us. There were around six or seven of them, about sixteen to eighteen years old, and all much taller than we were. They were all white, sporting unkempt clothes and even more unkempt teeth. They were from the rough part of town, and all of them were familiar to us. They were known in the town for being real hell-raisers and were often in trouble with the law.

Naturally Tan

Naturally Tan